Semiconductor Sourcing Strategy

The phrase ‘semiconductors shortage’ has been a constant headline for years. From automobiles and home appliances to industrial equipment and AI systems, virtually every product now depends on semiconductors. In this environment, ensuring a stable supply is no longer an issue that the procurement department alone can solve. What companies need today goes beyond the traditional question of ‘where to buy’ that has long defined purchasing strategy. In addition, the focus must shift to how to integrate the supply capability into entire Sourcing Strategy — a strategic mindset that extends far beyond conventional price negotiations.

■Economic Security in semiconductors

"Economic Security in semiconductors” actually began taking shape as early as the 1960s

“Economic Security in Semiconductors” actually began taking shape as early as the 1960s. At first glance, that may sound surprising.

Back then, Japan’s semiconductor industry—often referred to as “Hinokuni semiconductors”—held more than 50% of the global market. Its rise was remarkable, but for the United States, it was also a growing concern. Washington argued that Japan’s technological dominance threatened the spirit of the 1960 U.S.–Japan Security Treaty, and on that basis pushed Tokyo to open its market to American semiconductor firms, securing at least a 20% share for U.S. products. Japan was also pressured to disclose export prices to address alleged dumping practices.

These demands culminated in the 1986 U.S.–Japan Semiconductor Agreement—perhaps one of the earliest examples of economic issues and national security concerns being negotiated as a single “package.”

What followed for Japan was an era of restructuring. Subsidiarization, divestitures, and a long chain of M&A reshaped the industry. Many of the once-dominant Japanese semiconductor companies eventually disappeared from the global stage, and by 2023 Japan’s share of worldwide semiconductor revenue had fallen to roughly 8%.

Interestingly, a similar dynamic can be observed today in the steel industry. China now accounts for more than half of global crude steel production, while the United States imposes additional tariffs of 25–50% on certain steel imports.

Industries may change and eras may shift, but the underlying power dynamics of “economic security” have a way of resurfacing—again and again, in familiar forms.

10 Trillion JPY Investment Race — and the ‘Guardrail Clause’ as a Test of Commitment

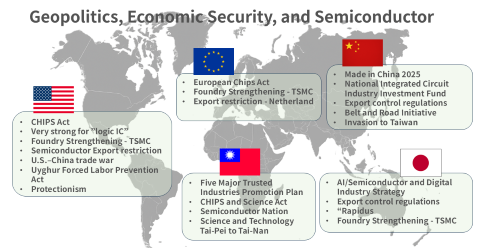

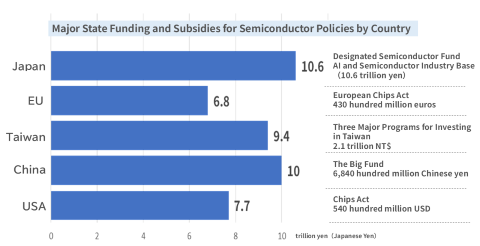

Today, the strategic moves of the U.S., China, Europe, Taiwan, and Japan (Image 1.1), along with their massive semiconductor investments (Image 1.2), are drawing significant global attention.

Image 1.1. - Economy Security

Image 1.2. - Funding for Semiconductor Policies

- USA「CHIPS Act」

- Europe「European Chips Act」

- China「National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund」

- Japan「AI・Framework for Strengthening the Semiconductor Industry Base」

Each represents an investment race exceeding the equivalent of 10 trillion Japanese Yen.

Building a semiconductor fabrication plant—whether advanced-node or legacy—requires more than one trillion yen in capital expenditure. Yet these subsidies are by no means “free gifts.”

Under the U.S. CHIPS Act, for example, companies must comply with the so-called guardrail provisions. These include restrictions on expanding production capacity in countries of concern (primarily China), as well as prohibitions on joint research involving products tied to national security. The requirements are stringent and far-reaching.

However, China remains not only a massive consumer market but also “the factory of the world,” home to a large concentration of EMS providers and OSAT companies. This creates a persistent tension between political decoupling and economic interdependence. It is therefore uncertain how effectively the guardrail provisions can function amid these two contradictory forces.

■Economy Security, Geopolitics and Supply Chain

"Go Get Chips"

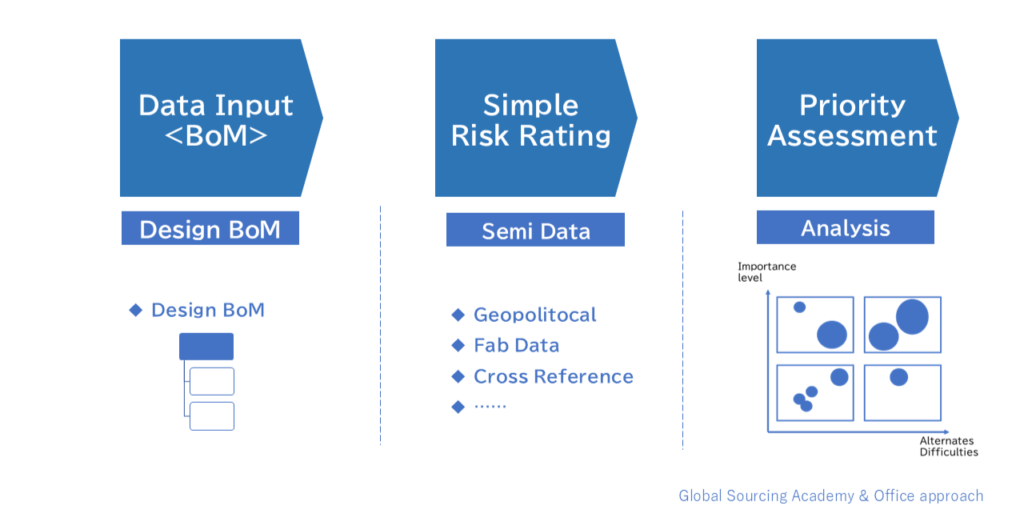

While these discussions on economic security are important from a high-level, strategic viewpoint, procurement teams on the ground often end up asking, “So, what should we actually do?” Our approach is to bring the conversation back to practical operations and encourage concrete examination within the development-procurement process.

- Evaluate the degree of substitution difficulty based on semiconductor information (such as fab locations and the presence of multi-fab production) and the availability of alternatives.

- Determine the priority of use

Apart from general-use ICs, the reality is that there are not many truly “compatible” semiconductor substitutes. The more practical approach today is to design products based on what can actually be procured and what carries lower sourcing risk. This kind of reverse thinking is becoming one of the most effective strategies in practice.